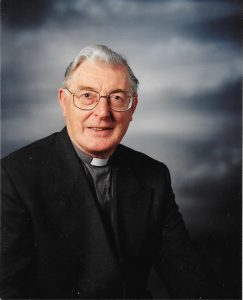

Ivor Harold Jones, 31 January 1934 – 7 April 2016

Address by The Rev’d Robert Dolman at the funeral of IVOR HAROLD JONES 22nd April 2016

It is a great privilege to articulate our thanks for the life and work of Ivor. His range of gifts was spectacular and he used them well; but he was also a memorable and graciously kind human being for whose guidance and friendship many have been grateful.

Ivor was born in Bradford in 1934 but his roots were Cornish; his father was a distinguished minister who became General Secretary of the Wesleyan Reform Union.

His secondary education was at the King Edward VII School in Sheffield which had begun life as a Wesleyan institution. Alongside his academic promise, Ivor was a keen games player, a footballer good enough to be chosen for Yorkshire Schoolboys, and to be offered a place in the Sheffield United Academy. He remained a very combative sportsman, and maintained his loyalty to Sheffield United.

In 1953 Ivor went up to Brasenose College, Oxford, where he read Classics and Music. He was the College Organ Scholar, and worked with the choir and orchestra.

Meanwhile the preaching and worship at Wesley Memorial Church, together with membership of the John Wesley Society, was a rich experience opening many intellectual and spiritual doors. So it was for the ministry of the Methodist Church that Ivor offered himself as a candidate. It was also at Oxford that Ivor met a fellow classicist, Kathleen Strand, with whom he was to enjoy a close and fruitful marriage lasting 54 years.

Ivor trained for the ministry at Wesley House, Cambridge. He performed excellently in the Theological Tripos, winning the Carus New Testament Greek Prize. This was followed by a year’s study in Heidelberg, a place to which he loved to return.

There then began the long career spent in theological education and ministerial formation. The first spell was at Handsworth College as Assistant Tutor, followed by his only venture into Circuit Ministry at Friern Barnet in the London Highgate Circuit. There Ivor introduced new elements into worship, including all age worship and a candlelit Christmas carol service, as well as providing congregations with the opportunity to discuss sermons.

This proved to be short lived as there followed the appointment as Ecumenical Lecturer at the Bishop’s Hostel, Lincoln. The daily round of Anglican liturgical worship and the immense care devoted to it made a lasting impression.

Ivor’s credentials as a scholar and teacher now firmly established, there followed an appointment to Hartley Victoria College, Manchester; then eleven years at Wesley College, Bristol; and fifteen years as Principal of Wesley House in Cambridge, before retirement in 1999.

The roles of College Tutors and Principals are many. Amongst them lies the pastoral care of students and the oversight of their growth into their vocational roles. Ivor was known and loved for his empathy towards those in any kind of crisis, and the care he took in Cambridge over the annual round of stationing students to their first appointments was legendary.

With a succession of talented colleagues, Ivor enabled the House to punch well above its weight in the Cambridge Federation of Theological Colleges. The college became a popular destination for visiting scholars from all over the world, and the buildings themselves were extensively used by other Christian bodies and by the Centre for the Study of Jewish-Christian relations.

Close relations were established too with South Africa, with the United College in Bangalore and the Henry Martyn Centre in Hyderabad. Wesley House did indeed make the world its parish. Ivor took a special interest in forging links with Eastern Europe, and must belong to a rather select group of Methodist ministers in his mastering enough Bulgarian to preach a message of hope to Christians worn down by Communist repression.

He was a passionate preacher, never dependent on manuscripts but always meticulously prepared. Hs public prayer was moving and simple, reflecting the piety of his nurture. In the midst of all this Ivor found time, burning a fair amount of midnight oil, for his own studies and for the writing of books and articles on. This earned him membership of learned societies and the editorship of the Epworth series of biblical commentaries; he wrote himself the volumes on the Apocrypha, on Thessalonians and on the Gospel of St Matthew, which he saw as ‘one of the great intellectual and spiritual challenges of all time, summoning from humanity all our imagination and courage’.

His magnum opus had a gestation period of thirty years. The Matthaean Parables was published in 1994. It is an exhaustive study of some six hundred pages. There are 591 names in the Index of Modern Authors. It required a mastery of biblical and modern languages and dexterity in using the full tool box of New Testament critical study, the literary and historical, the rhetorical and the sociological.

The book is like an archaeological dig as it patiently sifts through the minute details of the ways in which Matthew uses several grammatical Greek constructs. But this was not just number crunching or high minded lexicography. The immensely detailed work firmly underpinned the conclusion that the earliest Christians spread the Gospel by word of mouth rather than by documents. Ivor was not afraid, gently but firmly, to challenge the work of leading continental scholars. A focused study of Jesus’s parables found in them a subversive counter balance to law and institution.

Ivor was not afraid to enter into new and controversial public arenas well removed from his primary expertise. He chaired the Methodist Connexional Committee on Civil Disobedience, skillfully holding together those who championed the primacy of conscience and those who argued that democracy could flourish only in a society that was stable. He was also deeply engaged in the study of bioethics and the European Genome Project. At a time when a somewhat different mindset from now prevailed he was courageously radical in his stances on matters of human sexuality.

It is small wonder that, because of this dazzling versatility, Ivor was so often described as a polymath; clearly he could have taught to a very high level nearly all the subjects in a theological curriculum.

Like Methodism itself, Ivor was ‘born in song.’ In Chapel services and around the piano at home he would sing twenty hymns each Sunday. Two of his own hymn tunes, Muff Field and Sharrow Vale, are named after Wesleyan Reform Union churches where he worshipped in his youth. Kathleen has spoken about his huge work on Hymns and Psalms which enriched Methodist worship for a generation. Until very recently Ivor edited the weekly music column in the Methodist Recorder, exhibiting his catholic taste and prodigious knowledge.

In 1988 Ivor gave the Cato Lectures at the Assembly of the Uniting Church in Australia. These were published under the title ‘Music a Joy for Ever’. Here he vigorously defended music as the primary Christian art. There is a Platonic strain in Christianity which is suspicious of music as seductive and leading to flabby sentimentality, compromising the toughness of the faith. Ivor’s apologia champions music rather as a gracious and providential preparation for the Gospel.

He longed for an appreciation within Methodism of the enriching and educative power of hymnody and music, and feared what he called ‘philistine puritanism’ and worship which was ‘word bound, book bound and preacher bound.’ At a practical level of musicianship, he was immensely helpful when his local Church, Wesley in Cambridge. underwent wholesale renovation, and was faced with the challenging task of installing the huge organ from the Eastbrook Hall in Bradford.

Behind the polymath and distinguished minister whose services to the Church we celebrate today, there lay a very human man. It is hazardous, perhaps impertinent, to seek to penetrate the secret of a fellow human being, but it is an act of love and gratitude to try to understand and express what he or she was and meant or, in the vernacular, what made them tick.

There were of course foibles, idiosyncrasies, vulnerabilities. In the days before spellcheckers, students at Handsworth College found merriment in parodying Ivor’s lush array of typological errors. There were mannerisms of speech and expression that invited mimicry in college reviews. There was an otherworldly rather disconcerting vagueness about diary commitments and the times of appointments. There was also the embarrassing occasion at Cambridge when the Principal locked himself out of his own College.

Then there were the occasional unpredictable volcanic outbursts of temper. One of these occurred when an iconoclastic student suggested that the Cambridge University arms had no place on the annual College photograph; after this episode students seeing storm clouds brewing warned one another, ‘Ivor’s in crest mode.’

To be fair, some of these explosions arose from a sense of angry injustice when Ivor felt that someone had been wronged or their achievement unappreciated. He was a fierce and stubborn champion of the underdog.

And Ivor worked far too hard. The word No was an underused part of his vocabulary. He could not but be aware of his many gifts and their unusual combination, and he aspired to the best stewardship of them, but incessant travel, multifarious committees and sheer toil often destroyed all semblance of a balanced life.

As with all of us, there were deeply moving moments in Ivor’s life, moments that altered perception and bestowed new depths of understanding. In a lifetime’s love-affair with music some of these moments were performances where particular pieces became stamped with indelible associations.

One such was a celebration of the Eucharist at the Ecumenical Community at Taize where amidst colour, lights and the playing of a Bach fugue, Ivor felt, to use the words of the poet George Herbert, that ‘Love bade him welcome,’ and that he had found new delight and rapture in the sacrament itself.

Indeed, at the heart of Ivor’s theology lay a theology of the heart summed up in his phrase, ‘Grace and love seeking rapture.’ Ivor was deeply moved by his probing the family likeness he found between the plain scriptural theology and the hymns of the Wesley brothers and the profound reflections of the Roman Catholic Hans Urs von Balthasar on the theology of beauty.

‘Grace and love seeking rapture.’ Ivor held that the grace of God is the basic rhythm of Christian life and mission. The glories of that grace radiate through the intimacies of human existence and transform them into the beauty of perfect love.

We saw the grace in Ivor in his intercourse with people of all kinds. He was generous in appreciation and the words ‘thank you’ that were so often on his lips proved his firm grip on the grammar of gratitude. We saw the grace powerfully when he accepted without complaint that his medical condition meant he no longer play his beloved organ. And it was grace that gave him the twinkling humour and lightness of touch that made him good company.

We saw the love in his spontaneous rapport with children and with cats; in his appreciation of simple pleasures; his tender care for his sisters Iris and Audrey as they grew infirm; above all in his love for Michael and Elisabeth and his grandchildren, and in his cherishing of Kathleen in the gentle intimacy and unfailing support they shared in sickness and in health.

‘Grace and love seeking rapture’. Ivor found rapture in his work, buried in the depths of a Greek lexicon and the painstaking study of the nuances of the New Testament. Maybe like the great New Testament scholar, Bishop Westcott of Durham, the words for him ‘seemed like shafts of light from heaven; he loved each word as an individual.’

But Ivor found rapture too in the heights in the soaring experiences of Christian praise graced by music. In retirement in Lincoln he served as a Duty Chaplain at the Cathedral. He cherished its history, its fabric, its sheer loveliness, and worship there became an experience of transcendent beauty. It was a place where children could ‘stand, sit or lie down and gaze, and wonder at such a place as this.’

Perhaps we could say in Charles Wesley’s famous words that Ivor Jones was a man himself ‘lost in wonder, love and praise.’